Extracorporeal Life Support Saves Lives in Severe Accidental Hypothermia

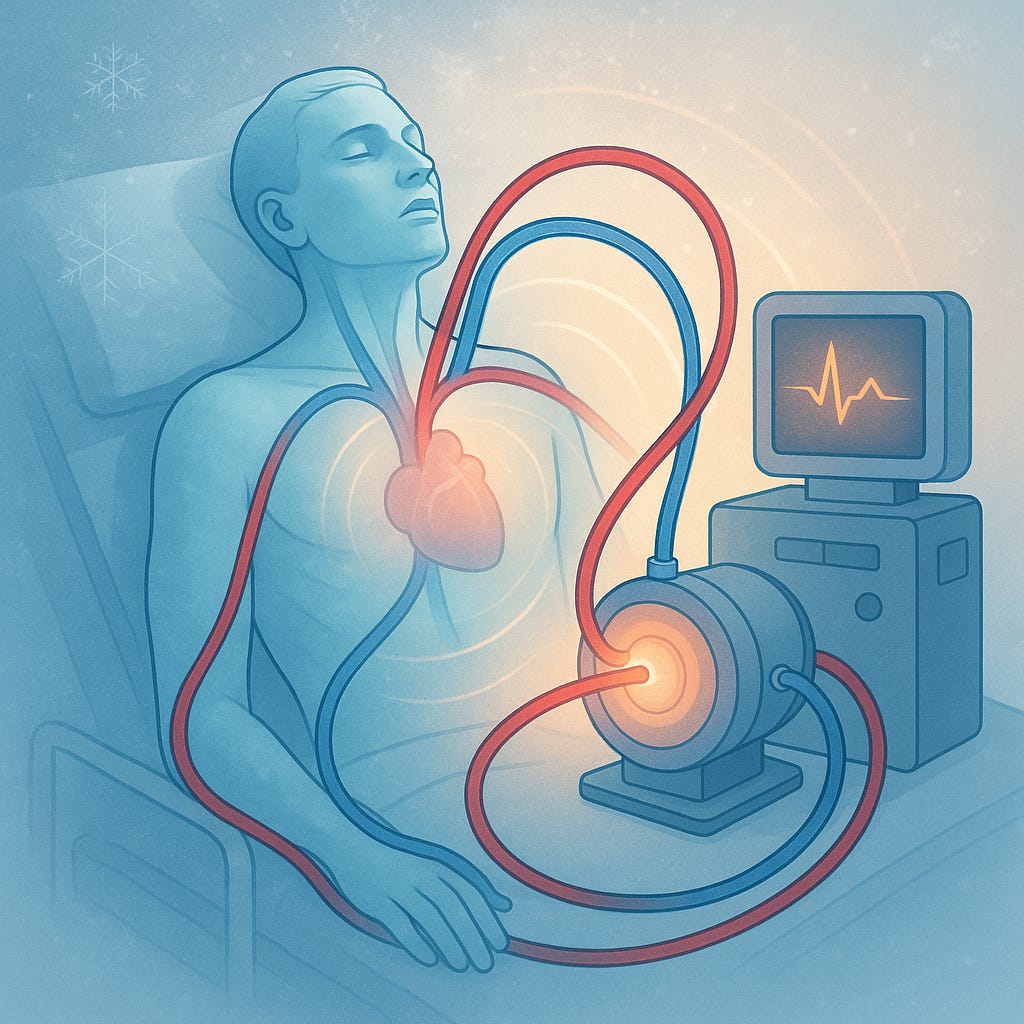

New evidence highlights how ECMO-based rewarming can restore heart function and neurological recovery in deep hypothermia cases.

Topline:

For patients with accidental hypothermia and cardiac arrest, extracorporeal life support (ECLS), primarily using ECMO, significantly improves survival and neurological outcomes compared with conventional rewarming methods.

Study Details:

Accidental hypothermia, defined as an unintentional core temperature below 35 °C (95 °F), can occur in any envi…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Just Healthcare to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.